That long-ago debut twirl took place years before Swagger started selling out 1,000-person venues with indelible Pride events featuring larger-than-life allies like Trina and Leikeli47. But if you knew, you knew: Those of us who attended that first edition could absolutely clock a new chapter in queer San Francisco hip-hop history.

As Swagger’s finale approaches, it seems like a good moment to reflect on what the party has meant for its artists and attendees. (This may not mean goodbye forever: Organizers hint that they might be back in the future for special events.)

“T

he community that has formed around Swagger Like Us is nothing short of beautiful, vibrant, colorful and inclusive. It’s been a beautiful journey, and I feel incredibly humbled by the trust that David and Kelly have placed in me,” says acclaimed vogue dancer and queer socialite Jocquese Whitfield, who has been hosting the party since that way-back first edition.

The party’s debut came mere months after a little-known “212” ingénue named Azealia Banks nonchalantly told The New York Times she was a bisexual. This was years before Lil Nas X came out with his 2019 track “C7osure,” a release that arguably ushered in the era of the mainstream gay rapper.

Nowadays, queer hip-hop has taken definite steps out of the underground. Streaming algorithms suggest LGBTQ+ performers like Doechii and Ice Spice, and veteran MCs Queen Latifah and Da Brat have finally gone public with their decided lack of heterosexuality, to the delight of legions.

Swagger was born to book queer hip-hop’s rising stars long before the majors were ready. On national tours as one half of the queer electro-pop duo Double Duchess, davOmakesbeats realized their home of San Francisco lacked inclusive, Black and Brown community functions that would “get” the lyrics and moves he and Krylon Superstar were delivering on stage. davO’s own Caucasity aside, the beats-obsessed, Maryland-born DJ wanted to feel that energy in his adopted City by the Bay.

“When I came to California, I would play Baltimore club tracks and no one would know what they were,” remembers davO, who was also the founder of the sweaty Chinatown basement party Blood Sweat and Queers. “I didn’t get it. I was like, ‘Not everybody listens to this?’”

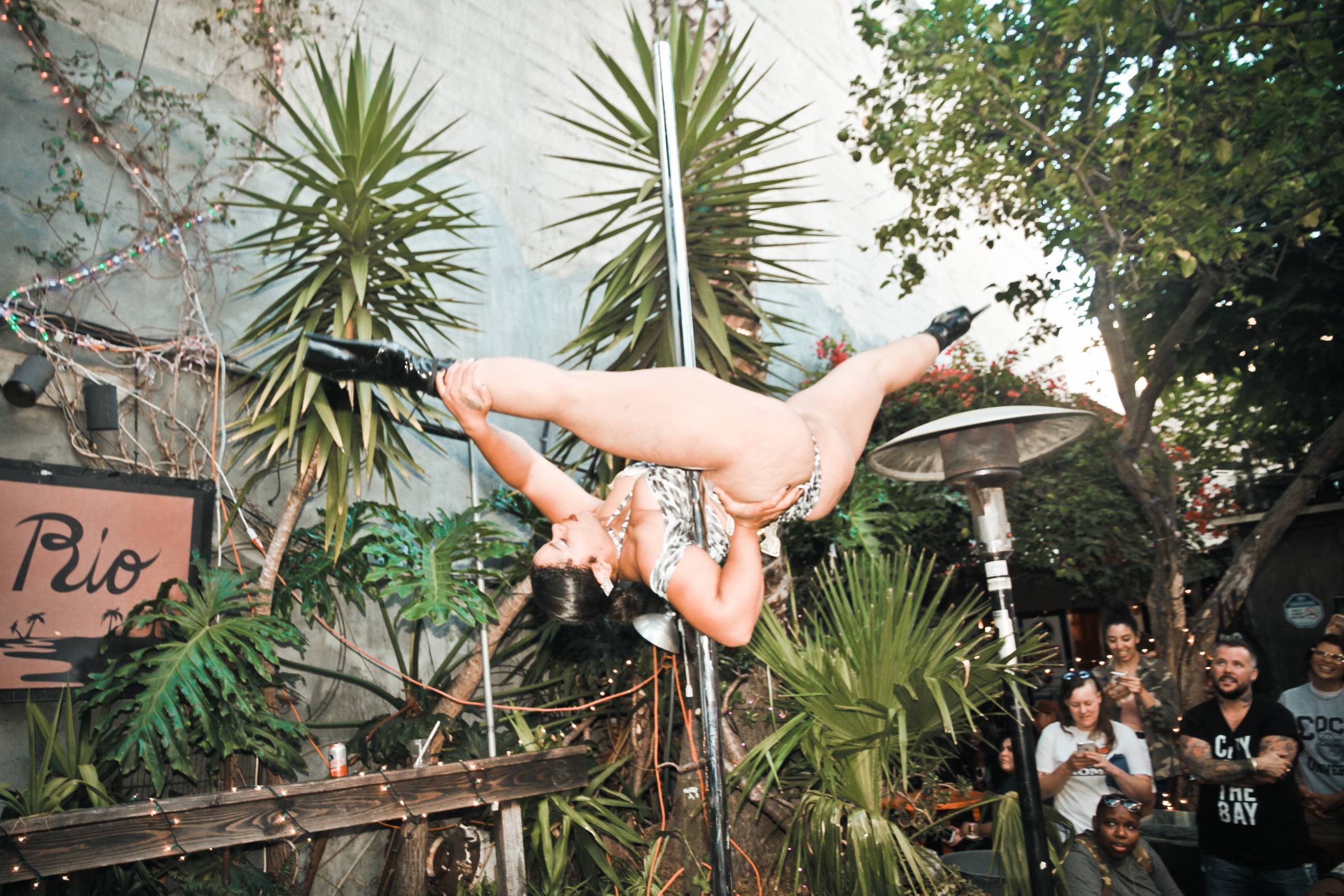

If it’s queer, immaculate vibes you’re looking for, you could do much worse than seek out davO’s eventual collaborator, Lovemonster. The multi-hyphenate creative with Haitian roots started producing events with their “Love canvases,” paint-spattered, clothing-optional performance-happenings they convened while attending their home state of New Jersey’s Rutgers University.

Today, they are successful curator and party producer in Sydney, Australia, where they live with their partner Spencer Dezart-Smith (a.k.a. boyfriend) — one of the founding DJs of Swagger Like Us — and their son. True to form, one of Lovemonster’s current events, Leak Your Own Nudes, is an underwear party. By the time they came together with davO over starting a new monthly function, Lovemonster was already a local nightlife heartthrob who curated the inclusive and foxy “go-go babes” at El Rio’s marquee soul music Saturday afternoon monthly, Hard French.

I

see now that this was one of the many golden ages of SF queer nightlife. In the early ’10s, you could drink affordably potent cocktails while grinding with sexy weirdos every night of the week: DJ Stanley Frank’s Viennetta Discotheque on Mondays, High Fantasy at Aunt Charlie’s on Tuesdays, Booty Call Wednesdays at Q Bar, Thursday nights at DJ Bus Station John’s Tubesteak Connection and avant-garde drag cabaret Club Something on Fridays at The Stud’s original location.

After a breakup, I wound up living with Lovemonster, Hard French promoter Tom Temprano and a passel of other sparkly queers and their pets in a ramshackle flat on South Van Ness Avenue. An easy drunken stumble from El Rio, our lair was the designated after for, uh, releasing the energy of Swagger’s daylight-hour parties. Despite a preponderance of shenanigans, we all got along surprisingly lovingly. The last of us didn’t leave that house until many years later, when the front staircase collapsed.